How to diagnose a collapsed trachea in a dog?

Other diseases of trachea and bronchus 2015 Billable Thru Sept 30/2015 Non-Billable On/After Oct 1/2015 ICD-9-CM 519.19 is a billable medical code that can be used to indicate a diagnosis on a reimbursement claim, however, 519.19 should only be used for claims with a date of service on or before September 30, 2015.

What is the ICD 9 code for trachea and bronch dis?

Other anomalies of larynx, trachea, and bronchus. Short description: Laryngotrach anomaly NEC. ICD-9-CM 748.3 is a billable medical code that can be used to indicate a diagnosis on a reimbursement claim, however, 748.3 should only be used for claims with a date of service on or before September 30, 2015.

What is the ICD 10 code for tracheostomy?

519.19 is a legacy non-billable code used to specify a medical diagnosis of other diseases of trachea and bronchus. This code was replaced on September 30, …

What is tracheal collapse?

Not Valid for Submission. 748.3 is a legacy non-billable code used to specify a medical diagnosis of other anomalies of larynx, trachea, and bronchus. This code was replaced on September 30, 2015 by its ICD-10 equivalent. ICD-9:

What is the ICD-10 code for Tracheomalacia?

Q32.0ICD-10 code Q32. 0 for Congenital tracheomalacia is a medical classification as listed by WHO under the range - Congenital malformations, deformations and chromosomal abnormalities .

What is the ICD-10 code for collapse?

R55ICD-10 code R55 for Syncope and collapse is a medical classification as listed by WHO under the range - Symptoms, signs and abnormal clinical and laboratory findings, not elsewhere classified .

What is the ICD-9 code for tracheostomy?

0 : Tracheostomy status. ICD-9-CM V44. 0 is a billable medical code that can be used to indicate a diagnosis on a reimbursement claim, however, V44.

What is the ICD-9 code for dysphagia?

Validation of ICD-9 Code 787.2 for identification of individuals with dysphagia from administrative databases. Dysphagia.

What is the code for faint?

2022 ICD-10-CM Diagnosis Code R55: Syncope and collapse.

What is diagnosis code R55 9?

Syncope is in the ICD-10 coding system coded as R55. 9 (syncope and collapse).Nov 4, 2012

What is the ICD 10 code for tracheostomy status?

Z93.0Z93. 0 is a billable/specific ICD-10-CM code that can be used to indicate a diagnosis for reimbursement purposes.

WHEN A tracheostomy is performed what is done to the windpipe?

Breathing is done through the tracheostomy tube rather than through the nose and mouth. The term “tracheotomy” refers to the incision into the trachea (windpipe) that forms a temporary or permanent opening, which is called a “tracheostomy,” however; the terms are sometimes used interchangeably.

Who did the first tracheostomy?

Despite the concerns of Hippocrates, it is believed that an early tracheotomy was performed by Asclepiades of Bithynia, who lived in Rome around 100 BC. Galen and Aretaeus, both of whom lived in Rome in the 2nd century AD, credit Asclepiades as being the first physician to perform a non-emergency tracheotomy.

What is the diagnosis code for dysphagia?

R13.10Code R13. 10 is the diagnosis code used for Dysphagia, Unspecified. It is a disorder characterized by difficulty in swallowing. It may be observed in patients with stroke, motor neuron disorders, cancer of the throat or mouth, head and neck injuries, Parkinson's disease, and multiple sclerosis.

What is the ICD-10 code for oropharyngeal dysphagia?

R13.12ICD-10 | Dysphagia, oropharyngeal phase (R13. 12)

What dysphagia means?

Dysphagia is difficulty swallowing — taking more time and effort to move food or liquid from your mouth to your stomach. Dysphagia can be painful. In some cases, swallowing is impossible.Oct 20, 2021

What is the ICd 10 code for bronchitis?

748.3 is a legacy non-billable code used to specify a medical diagnosis of other anomalies of larynx, trachea, and bronchus. This code was replaced on September 30, 2015 by its ICD-10 equivalent.

What is the ICd-9 GEM?

The GEMs are the raw material from which providers, health information vendors and payers can derive specific applied mappings to meet their needs.

What is a collapsed lung?

A disorder characterized by the collapse of part or the entire lung. Absence of air in the entire or part of a lung, such as an incompletely inflated neonate lung or a collapsed adult lung. Pulmonary atelectasis can be caused by airway obstruction, lung compression, fibrotic contraction, or other factors.

What causes a lung to collapse?

This may be caused by a blocked airway, a tumor, general anesthesia, pneumonia or other lung infections, lung disease, or long-term bedrest with shallow breathing. Sometimes called a collapsed lung.

What is tobacco dependence?

tobacco dependence ( F17.-) (at-uh-lek-tuh-sis) failure of the lung to expand (inflate) completely. This may be caused by a blocked airway, a tumor, general anesthesia, pneumonia or other lung infections, lung disease, or long-term bedrest with shallow breathing. Sometimes called a collapsed lung.

What is the best treatment for tracheal collapse in dogs?

Treatment of tracheal collapse is first geared toward medical management with anti-inflammatory steroids, cough suppressants, and sedation as needed. Bronchodilators are commonly used but likely show minimal benefit with solely tracheal disease present. Prednisone is often the first line corticosteroid ...

What breed of dog has a tracheal collapse?

Tracheal collapse is most common in middle aged to older small breed dogs with the Yorkshire terrier, Pug, Chihuahua, Poodle, and Maltese being over represented. The condition can be congenital but is often caused by progressive generative changes of the tracheal cartilages (tracheomalacia) leading to a loss of tracheal integrity ...

Can tracheal collapse be detected on a radiograph?

Tracheal collapse can often be diagnosed based on a combination of signalment, clinical signs, and thoracic radiographs. If tracheal collapse cannot be captured on plain radiographs then bronchoscopy (Figure 1) or fluoroscopy may be needed to evaluate for a dynamic collapse.

Can a tracheal stent be placed in combination with a tracheal stent

Although tracheal collapse is a chronic process with life threatening potential, many patients can do well long term with medical management alone or in combination with placement of a tracheal stent, if needed.

Clinical Signs

If a dog is experiencing tracheal collapse or malformation of the trachea, s/he will exhibit signs including:

Diagnosis of Tracheal Collapse

If your dog consistently exhibits any of these clinical signs, schedule an appointment with your veterinarian. Your vet will likely suspect tracheal collapse if your pet appears to have difficulty breathing or shows any other associated signs. S/he will also factor in breed during the evaluation.

Treatment

Unfortunately, there is no cure for tracheal collapse. Treatment focuses primarily on limiting the clinical signs that the pet is experiencing. That being said, while there is no complete cure, most dogs respond well to treatment and may go years without major complication.

Tracheal Stenting

Though most pets never need more than daily medications, there are others that need more interventions to save their lives or to improve their quality of life. Consequently, dogs that present with more severe signs (such as passing out or turning blue) or that are no longer responding to medical therapy may be candidates for tracheal stenting.

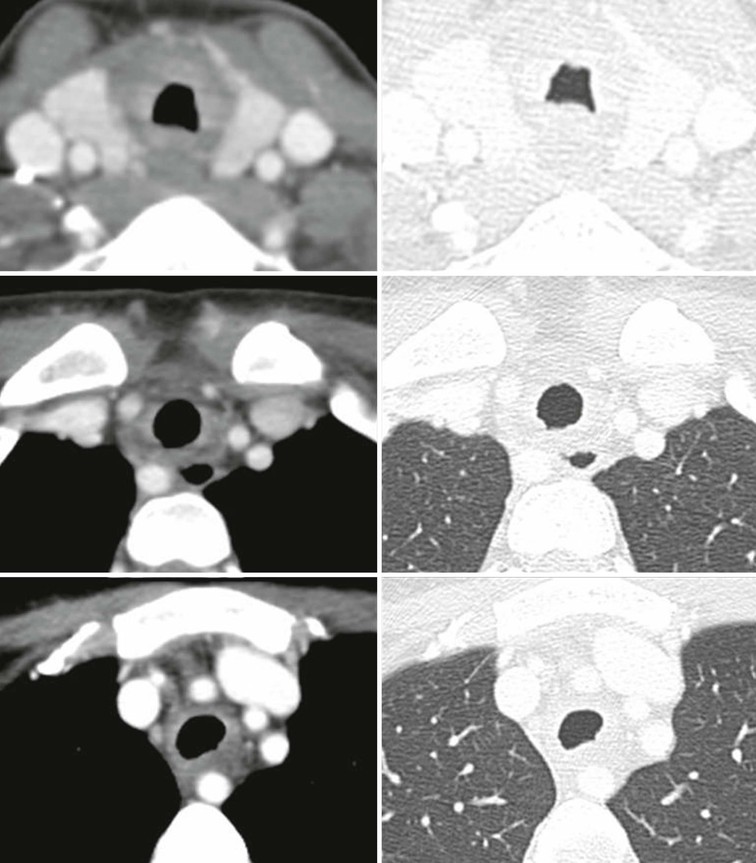

Images

Tracheal Collapse (Before): This chest radiograph (x-ray) of a chihuahua shows a severe degree of tracheal collapse. The black arrows are pointing to the normal portions of trachea which contains air (which appears dark gray on x-rays). Whereas the white arrows show a region of complete tracheal collapse with a complete lack of the dark gray gas.

Monitoring

When a dog is being managed medically, s/he will likely need recheck appointments with a veterinarian at least every 6 to 12 months for a routine evaluation and medication adjustments. Those with a tracheal stent need periodic follow up appointments with their internist or surgeon.

Complications of Untreated Tracheal Collapse

If you suspect that your dog has tracheal collapse, we recommend scheduling an appointment with your vet. In time, if untreated, tracheal collapse will likely worsen and the dog may experience:

What are the grades of tracheal collapse?

Tracheal collapse is classified into four grades: Grade 1: The important cells that form the tracheal lumen, a structure that supports your dog's trachea, are reduced by approximately 25%, but the cartilage is still normal shaped. Grade 2: The tracheal lumen is reduced by approximately 50% and the cartilage is partially flattened.

How to tell if a dog has a tracheal collapse?

In addition to a honking cough, there are other signs that could indicate tracheal collapse. Some of them include: Difficulty breathing. Coughing when you pick your dog up or apply pressure to their neck. Vomiting, gagging, or retching associated with the coughing.

What is the trachea of a dog?

The trachea is a flexible tube with sturdy c-shaped rings of cartilage. These cartilages keep the trachea open for air to get in and out of the lungs. Tracheal collapse is a progressive respiratory condition that occurs when these tracheal rings of cartilage collapse. It can cause your dog to have breathing problems as the windpipe collapses.

What tests are used to check for tracheal collapse?

Other tests: These could be blood tests, a check-up that includes urinalysis, blood count, chemistry panel, and/or heartworm testing to check for conditions that may cause coughing. Other methods like radiographic imaging can be used, but these might not be enough to diagnose tracheal collapse on their own.

Why does my dog cough when he has a trachea?

If their trachea begins to collapse, you may notice your dog producing a honking cough. This happens as the air pushes through the collapsing rings of cartilage.

What happens if a dog's trachea collapses?

A dog with tracheal collapse will experience bouts of respiratory distress. These episodes can be violent and last a few minutes until they resolve themselves. Obesity and humid weather are other factors that could bring out the signs of tracheal collapse in your dog.

Why does my dog cough when he has a windpipe collapse?

It can cause your dog to have breathing problems as the windpipe collapses. This can result in a harsh dry cough. In most cases the cause of tracheal collapse in dogs is unknown. However, it may be a congenital disorder.

Popular Posts:

- 1. what is the icd 10 code for leukoencephalopathy of unknown etiology

- 2. icd 10 code for lump in neck

- 3. icd-10 code for brain hemorrhage

- 4. icd-10 code for medical necessity non-emergency transportation

- 5. icd 10 code for end stage osteoarthritis

- 6. what would the icd 10 cm code be for staphylococcus aureus arthriti of the right wrist

- 7. icd code for right knee locking

- 8. icd 10 cm code for ulcer with necrosis of the muscle of the left ankle

- 9. icd 10 code for hep c in pregnancy

- 10. icd 10 code for perforated duodenal ulcer